[Mount Washington funicular]

On the north side of town, across the Allegheny River, in the Manchester and Mexican War Streets neighborhoods, stood steep narrow townhomes and big old Victorian Mansions like Hopper painted. The areas attracted residents escaping the dense inner-city in the late 1800s, who took the streetcar downtown. Here also resided a museum dedicated to the city's most famous son: Andy Warhol.  Though the consensus seems to be that no one leaves Pittsburgh, Warhol did. His brother, however, still runs an auto body business here.

Though the consensus seems to be that no one leaves Pittsburgh, Warhol did. His brother, however, still runs an auto body business here.  [Paul Warhola Scrap Metal] I guess they both ended up artisans.

[Paul Warhola Scrap Metal] I guess they both ended up artisans.

Growing up in an industrial city like Pittsburgh might explain Warhol's industrial approach to art. He mass-produced everything, and used brand names as subjects.  One of his "sculptures" reproduced a Heinz tomato ketchup box. The piece was donated by Mrs. Henry J. Heinz II of the local ketchup empire, whose factory sign Warhol would have grown up seeing.

One of his "sculptures" reproduced a Heinz tomato ketchup box. The piece was donated by Mrs. Henry J. Heinz II of the local ketchup empire, whose factory sign Warhol would have grown up seeing.

Pittsburgh was rife with other pop culture icons, too. The first Nickelodeon opened here in 1905, which may be why eventual producer David O. Selznick started by opening a Nickelodeon in Pittsburgh. (Later, George A. Romero shot Night of the Living Dead! here.) Pittsburgh was also home to the world's first gas station,  opened in 1913, the same year Hopper's painting Sailing sold.

opened in 1913, the same year Hopper's painting Sailing sold.

Painter Mary Cassatt came from a well-to-do Pittsburgh family. Hopper wrote in a letter about his Paris days: "As for Mary Cassatt, I did not know her in Paris, although it is possible our times overlapped slightly. After all, why should I know her? I was only an unknown American art student at that time." You can almost hear his resentment at his talent being unrecognized. He also never visited the Paris salon of Gertrude Stein, who was born on Pittsburgh's North Side.

20090228

168 Pittsburgh, PA: Brands

20090227

167 Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh?

Sightseeing, I found a city different than the one advertised. The city's Web site touts Pittsburgh as the only city to consistently rank as one of the top 10 Most Livable Cities in North America. But the local alternative newspaper Pittsburgh City Paper confessed, "…we're loath to change, unfriendly to newcomers, resistant to new initiatives, convinced we're cursed." The Web site also said that Pittsburgh's violent crime rate was considerably below the national average; however, the newspaper headline screamed, "Forty-fourth city homicide pushes total past all of last year's."

Maybe that's one reason that the architectural highlight downtown was H.H. Richardson's Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail, whose 325-foot tower dominated the skyline for years. Built with Pittsburgh iron and glass, Richardson's fanciful design included a Bridge of Sighs,  modeled on the Venice prison's sixteenth-century bridge by that name. The stairways and arches inside made it look like an Escher painting.

modeled on the Venice prison's sixteenth-century bridge by that name. The stairways and arches inside made it look like an Escher painting.  Richardson's health was failing during construction, and he asked, "If they honor me for the pygmy things I have already done, what will they say when they see Pittsburgh finished?"

Richardson's health was failing during construction, and he asked, "If they honor me for the pygmy things I have already done, what will they say when they see Pittsburgh finished?"

Another highlight was the library, which, as expected, was a Carnegie library.

Another downtown theater had on its Art Deco backside a sign that showed Pittsburgh's past not only because it was studded with white filament light bulbs but also because it didn't advertise "movies" but instead "photoplays." Or maybe this was just another Pittsburgh phrase of speech. The local accent sounded to my ear like a cross between Boston and Southern. They pronounced Downtown and South Side as "Dahntahn" and "Sahside," and the Steelers are "Stillers." And they had a whole different language in which nosy neighbors were called "nebby," and to clean house was to "redd up."

An usher with a nametag that read "Annie" snuck me in and told me about the place. She had a puffy face with a birthmark under her eye, and her short hair was irregularly cut. I told her that I saw a sign that said it was called the Gaiety.

"I didn't know it was called that at all," she said. "When you go out this side on Fort Duquesne, you can see the Ritz. That was built in 1906. They had live theater; there was live people. You used to have a lot of theaters down here, then. We had the Duquesne Theater and the Lyceum Theater; those were both torn down. This is a beautiful theater. There used to be a mural on that wall right there. But nobody can remember what it was."

At the Prima Espresso deli, the counterman John had a large face with olive skin and dark, thick eyebrows above half-lidded green-brown eyes. I asked him if people in Pittsburgh were isolated. He answered with an accent like a Brooklyn tough, but was soft-spoken and thoughtful.

"Yeah. Pittsburgh, for as many people that are trying to drive the city forward, there are that many people still holding it back. There are people still complaining about why do we need a new ballpark. I came from a small town in Northwest Pennsylvania, and I find that there's a small-town mentality here holding it back. They're trying to separate themselves from the rest of the country by saying, 'Oh, don't leave Pittsburgh; we have such good things here.' If we're so good, why do we need a new baseball stadium?"

20090226

166 Pittsburgh, PA: Lucky

The museum's founder, Andrew Carnegie, was a man of paradoxes, like Hopper was a man of silences. Carnegie lived like a king yet hated the ruling class; made millions but gave it all way. He built a library for any town in the U.S. that subsidized 10% of the costs. And he founded many philanthropic entities, including this university and its museum. He envisioned it as collecting the "Old Masters of tomorrow" (a great way to describe Hopper).

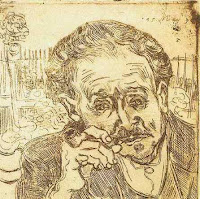

The Carnegie was home to Van Gogh's only etching. The etching shows Paul Ferdinand Gacher, a doctor who also was an etcher and probably taught Van Gogh the technique. Similarly, Hopper also had his earliest success with etching and learned from his friend Guy Pene Du Bois. Hopper was also famous for his renditions of buildings, and The Carnegie had a Hall of Architecture inspired by the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and the largest collection in the U.S. of plaster cast architecture, a common practice in the late 1800s.

Hopper's idol Thomas Eakins was represented by a portrait of Joseph R. Woodwell,  who was in turn represented by a painting titled Pennsylvania House.

who was in turn represented by a painting titled Pennsylvania House.  Beside Henry Ossawa Tanner's painting Christ at the Home of Mary and Martha was a sign explaining that Tanner was born in Pittsburgh's Hill District and eventually studied with Eakins.

Beside Henry Ossawa Tanner's painting Christ at the Home of Mary and Martha was a sign explaining that Tanner was born in Pittsburgh's Hill District and eventually studied with Eakins.

At the museum store, I found Cape Cod Afternoon on the side of a kaleidoscope for sale. It made me think how using him as a lens had led me to see ever-shifting patterns across the U.S. I interviewed the worker behind the store counter: a woman with sallow skin, freckles, a sharp nose, and a set jaw. She had gray hair and wore a pink shirt and a long, thick gold rope that followed the upper hem of her denim jumper.

"I don't think of the people in Pittsburgh as isolated. Every now and then, we get homeless people here or in the library next door, and of course, I don't commune with those people. But there are times when very lonely people have hung out here. Sad to say that certainly everywhere there are people that fit into that category." She suddenly asked, "What years did Hopper live?"

"1882-1967."

"That means that his last few years he was quite up in years."

"But he was still painting."

"He still painted," she sighed. "He was physically still active. Oh that was fortunate. And his wife outlived him. That was lucky for him, that there was someone there for him."

20090225

165 Pittsburgh, PA: Decay

But I had come to see Cape Cod Afternoon. A sprawling Cape Cod house sits in a summery succotash of field beneath a faded yellow and purple sky. Odd ells of black jigsaw through the painting, the windows are all irregularly shaped, and it has the most haphazard horizon line I have seen in any Hopper painting.

Also, uncharacteristically, Hopper worked at the site outdoors. Jo noted: "I remember the day he brought the canvas home with the most gorgeous blue sky & white clouds flying, tearing themselves in rush forward from behind top of roofs-violent & stirring. But alas E. has changed it-said the sky too important--& no matter how gorgeous & stirring-he not willing to sacrifice the house for the sky." She added, "shed goes in like entrance to a tomb."

About this one, Champ was more reticent. "I never studied Hopper's paintings in any formal way," he cautioned, "But I like his works that have figures in them more than something like Cape Cod Afternoon. Because of that traditional sense of melancholy or something, some kind of tension. There is some element of story or a sense that something has happened or is about to happen: that I like."

"Cape Cod Afternoon," I informed him, "won the first W.A. Clark Prize at DC's Corcoran. Eleanor Roosevelt came and saw it and shook Hopper's hand and said, 'I can see it better if I stand a little farther away from it.'"

"Isn't that great?" Champ chuckled, "Always the politician."

About Hopper’s isolation relating to America or Pittsburgh, he refused to comment.

Luckily, after he went back to his office, I was joined in front of the painting by an older couple. She had bright red lipstick, swollen ankles, and a big wart on the bridge of her nose. She carried a tan purse and wore a blue cotton dress with roses on it. She also flaunted sandals and many rings. He was a portly, with brown eyes and white eyebrows on which rested a leather Greek-fisherman's cap.  A rich blue T-shirt covered his ample belly. He wore shorts, white socks, and faded blue tennis shoes. She was from Pittsburgh, but her male friend was an old colleague from the sixties who had often visited her in Pittsburgh for years and was doing so again.

A rich blue T-shirt covered his ample belly. He wore shorts, white socks, and faded blue tennis shoes. She was from Pittsburgh, but her male friend was an old colleague from the sixties who had often visited her in Pittsburgh for years and was doing so again.

"I think sometimes we [in Pittsburgh] are backwards, provincial," she chewed out of a mouth that moved quickly but didn't open much. "I grew up in New York, but I've lived here since '67 so I consider myself to live in Pittsburgh. I like the friendliness of Pittsburgh. You'll find that Pittsburgh is friendly. Unlike New York where they don't meet your eyes."

"Pittsburgh," she explained, "is sort of isolated from itself, in that there are so many rivers. We have more bridges than even Venice.

"We have a huge aging population," She noted. "Second-largest outside of Dade County, Florida. So many of the families, the parents and grandparents have stayed here. And their children stay. They live in their own little group. They probably feel no need to reach out."

She shot a hand to her chin. "That's not a good impression of what Pittsburgh's all about. I like Pittsburgh, though."

Though not from Pittsburgh, the man offered his two cents. "While Susan has said that many people here are in neighborhoods and holding it together, I do agree with Hopper's vision. I think basically we're all very isolated. Lonely, sad: I think he captures that.

"The whole complex [in Cape Cod Afternoon] is going into decay. Perhaps this was a farm here, but all of it is decaying. He just wants to remind you that a family once lived here. The light has a problem getting to it. You're drawn to this black, almost into this house where the family and people once lived. You're drawn in to the mystery of the vanishing of things. In a way, it's like an Egyptian pyramid. It's like some generalized sense of passing of life.

"I think probably as an artist, [Hopper was] more interested in light. But we as viewers look at that and go, 'Oh God.' But as far as [Hopper] being an artist that captures the American scene. I don't see it as only American."

20090224

164 Pittsburgh, PA: Champ

[Carnegie Museum of Art]

"Nyack's a great place to grow up," he crowed. "You're close enough to take advantage of all that New York City has to offer, but you're not living there. And there's enough of a small-town element to counterbalance the suburban element so it wasn't like growing up in Levittown."

"Pretty Penny," I asked, "didn't have the brick wall when you were growing up, did it?"

"Well," Champ sniffed, "it had another brick wall when Helen Hayes lived there, though she wasn't quite as reclusive as Rosie O'Donnell. Neighbors of ours across the street worked for Helen Hayes for a while, so I actually got to go inside the house, and I swam in the pool. And there didn't seem to be anything wrong with the house that Rosie O'Donnell needed to say, 'strip it to the walls; add another three feet to the brick wall; close the big iron-gate' (which was never closed when I was a kid); and then move out.

"I worked at the Nyack library when I was in college, and somebody that I worked with there was living in the apartment upstairs of Hopper's house. She and her husband were sort of caretakers of the place. The general population [of Nyack] kind of knows of its existence but probably has never been there.

"I recognize a number of buildings as local buildings, although he's taken them and put them into a different context. There's one where it's a building in Nyack, the storefront.  In his picture, it recognizably has become his building. But that four-square with the central column and central path is easily identifiable in any town.

In his picture, it recognizably has become his building. But that four-square with the central column and central path is easily identifiable in any town.

"I tend," he frowned, "to see Hopper as more of an urban artist. Or more concerned with urban themes. What speaks to me is a kind of alienation and melancholy. And Nyack is not that kind of place, and I'm sure even less so when he was living there. It's a neighborly place, a very community-oriented place. Maybe having grown up there [in Nyack], it was his response to New York that made it onto the canvas. He may have found a kindred spirit in the New York experience. Because he was not the most forthcoming person.

Champ wanted to talk about the Carnegie’s other Hopper.  Sailing was painted in 1916, before my cutoff point, but it was important to Hopper’s life. It was the single oil painting he sold as a young artist, bought from the famous so-called "Armory Show" in New York City that introduced Americans to Modernist painters. Its fame resurfaced in 1981 when x-rays revealed an early self-portrait underneath.

Sailing was painted in 1916, before my cutoff point, but it was important to Hopper’s life. It was the single oil painting he sold as a young artist, bought from the famous so-called "Armory Show" in New York City that introduced Americans to Modernist painters. Its fame resurfaced in 1981 when x-rays revealed an early self-portrait underneath.  Once you know it's there, the self-portrait is obvious. Hopper used dark blue to cover up the more visible parts of the portrait. The coloring of the sky mimics his face sideways, which looks downward in the current canvas's orientation. A diagonal slash in the painting originally demarcated the collar of Hopper's jacket, while other ridges in the paint's surface clearly show the shape of the head and ear.

Once you know it's there, the self-portrait is obvious. Hopper used dark blue to cover up the more visible parts of the portrait. The coloring of the sky mimics his face sideways, which looks downward in the current canvas's orientation. A diagonal slash in the painting originally demarcated the collar of Hopper's jacket, while other ridges in the paint's surface clearly show the shape of the head and ear.

"Hopper," Champ pointed out, "won a Carnegie Prize. He also, earlier in his career, sent the Carnegie a painting, La Berge, when he was doing French subjects. They rejected it, and that was sort of a defining moment. The Carnegie sent it back, and he destroyed it. He went back and started to paint American subjects."

20090223

163 Pittsburgh, PA: Dinah and Michelle

Dinah graciously offered not only to put me up but also to introduce me to some friends. That night, Dinah had arranged for us to have dinner with Michelle, a willing interviewee with girl-next-door looks. We all went to a church. Well, a church that was now a brewpub; rather fitting, I thought, in this town known for blue-collar steel-mill workers who worship a good quaff after a hard day on the job.

Our Lady of the Holy Ale (my name for it) was on a major North Side street. The nave was now painted bright blue and held the brewing apparatuses (religious gear to the current denizens).  We sat in pews.

We sat in pews.

When I asked my question, Michelle thought for a while then breathed in deep and prefaced, "You really want an answer? I think people in Pittsburgh are some of the most isolated, parochially minded people I've ever met in my life. A lot of them never ventured out beyond Western Pennsylvania, nor do they want to. This is based on empirical research. I've lived here ten years, and people still can't pronounce or spell my name."

"Michelle?" I joked.

"That either," she laughed. "They think I'm saying Miss O. Honest to God. I don't think I have enunciation problems."

Switching gears, she shrugged, "It's been a really good starter city for me. I came here when I was twenty. I've sort of become an adult here. Cost of living is good. People in general are very friendly. I could do a hell of a lot worse than Pittsburgh. But sometimes it's a little bit suffocating 'cause you have to drag the river for somebody who's read a book."

Dinah deadpanned, "Yeah the smart-guy factor is definitely not good."

"Smart anybody factor," Michelle tacked on.

"I think that's typical of our culture overall," Dinah posited, and Michelle nodded. "Individually," Dinah continued, "I don't feel that way [isolated]. But a lot of people are in their own little world. In Pittsburgh, people live here, and they die here, generation after generation. Pittsburgh's its own microcosm, not worldly. But a lot of people come here from other places, and that kinda spruces things up a little bit."

Michelle wrinkled her nose, "I still don't think it's very diverse. I think about leaving here sometimes because it is really white bread. There's a lot of incest in hiring. You know, if they went to the same college, especially Pitt or Notre Dame. I think our priorities are a little bit screwed. I had to work my ass off, and I got an academic merit scholarship. But somebody who can't spell his own name gets a free ride through his school because he can kick a football."

20090222

162 Pittsburgh, PA: Cape Cod Afternoon

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Cape Cod Afternoon

In Pittsburgh, I was hosted by Dinah, a long-lost childhood friend who had a popular radio show on the local independent station. "The very first commercial radio station was here in Pittsburgh," she informed me, "It was called KDKA. And they're still KDKA." I learned quickly that nothing changes much in Pittsburgh, including its industrial feel. I sneezed as Dinah drove me around town and she sneered, "The air quality [here] is still not great. I went water-skiing once in the rivers around here, and it felt like it took a week to rinse the film off."

The town began in 1759 as Fort Pitt (named for Great Britain's Prime Minister William Pitt) on a triangle of land where three rivers meet: the Monongahela, Allegheny, and Ohio. The young surveyor George Washington noted that this location was "well situated" because Pittsburgh's rivers connected to the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico.

In the late nineteenth century, Pittsburgh labeled itself "the natural point of distribution for the most prosperous section of the United States." Soon it called itself also "workshop of the world." To supply Fort Pitt, the army tapped the area's local coal, which was later deemed the single most valuable mineral deposit in the U.S. Taking advantage of the local ore, a small forge opened in nearby Millvale in 1858 that spawned Andrew Carnegie's iron and steel empire that is almost synonymous with Pittsburgh.

Industry flourished in Pittsburgh in the late 1800s. Companies that evolved into ALCOA, PPG (Pittsburgh Plate Glass), Pittsburgh Paint, and of course, America's ketchup: Heinz. Commerce led to the development of Pittsburgh's "Wall Street," the Fourth Avenue financial district, home to Andrew Mellon's bank. By 1908, only New York City held more money than Pittsburgh. As stocks and then steel folded through the 1900s, so did Pittsburgh.

Dinah began pointing out landmarks of the town's legacy. "That's the  U.S. Steel Building," she said, "the big rusty brown building made out of steel." A notch halfway up the building made it look like a giant rusty I-beam. The Aluminum Company of America

U.S. Steel Building," she said, "the big rusty brown building made out of steel." A notch halfway up the building made it look like a giant rusty I-beam. The Aluminum Company of America  (ALCOA) Building was built of aluminum, and Pittsburgh Plate Glass had an all-glass building.

(ALCOA) Building was built of aluminum, and Pittsburgh Plate Glass had an all-glass building.  The United Steelworkers of America was hatch-marked to form diamond windows.

The United Steelworkers of America was hatch-marked to form diamond windows.  "Do you see the one," Dinah asked, "with the kind of flagpole coming out of it? I call that the

"Do you see the one," Dinah asked, "with the kind of flagpole coming out of it? I call that the  Phillips head screwdriver building!"

Phillips head screwdriver building!"

Resting beneath a sheer cliff along one river sat a grand old railroad station with P&LERR written in big letters across the top. It had been forged into a mall with upscale shops called One Station Square. Dinah said,  "This beautiful old building is Station Square, the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad Building. Pittsburgh being a railroad town and all. The windows in Station Square were painted black in World War II so as not to be seen, and no one remembered that there was

"This beautiful old building is Station Square, the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad Building. Pittsburgh being a railroad town and all. The windows in Station Square were painted black in World War II so as not to be seen, and no one remembered that there was  stained glass underneath it until they renovated it."

stained glass underneath it until they renovated it."

20090221

161 Youngstown, OH: Grist for the Mill

I drove downtown over the Market Street Bridge, which spanned the Mahoning River and the train lines paralleling the river. In the valley to my left lay a huge steel mill, a boxy turquoise corrugated tin building surrounded by mud and a fan of railroad track spurs. The meters where I parked near the convention center had plastic bags over them that read: "Welcome visitors, 2-hour free parking." Napoli Pizza and the Draught House bar were two of the few businesses still open. Silver's Vogue Shop for men's clothes in fact displayed clothes that were very out of vogue.

I drove downtown over the Market Street Bridge, which spanned the Mahoning River and the train lines paralleling the river. In the valley to my left lay a huge steel mill, a boxy turquoise corrugated tin building surrounded by mud and a fan of railroad track spurs. The meters where I parked near the convention center had plastic bags over them that read: "Welcome visitors, 2-hour free parking." Napoli Pizza and the Draught House bar were two of the few businesses still open. Silver's Vogue Shop for men's clothes in fact displayed clothes that were very out of vogue.

On the tourism board's map of things to see in town, half were churches. Brian had said, "The people who came here brought their religions with them and then they all wanted their own." Eastern European tear-drop-shaped onion domes led me to the 1913 Sts. Peter and Paul Ukrainian Orthodox Church, which was right by Holy Trinity Ukrainian Church.  Our Lady of Mount Carmel church on a hill east of downtown flew both the American and Italian flags. Right next door, Sts. Cyril and Methodius flew Slovak flags. Even the Baptists were split into three congregations: the Tabernacle Baptist Church, Union Baptist Church, and Metropolitan Baptist Church.

Our Lady of Mount Carmel church on a hill east of downtown flew both the American and Italian flags. Right next door, Sts. Cyril and Methodius flew Slovak flags. Even the Baptists were split into three congregations: the Tabernacle Baptist Church, Union Baptist Church, and Metropolitan Baptist Church.

In a town dominated by industrial hulks and old churches, the city park was a beloved haven. Mill Creek Park was home to one mill still left in Youngstown. Though not a steel mill, Lanterman's Mill operated as a fully working gristmill, just as it did when opened in 1846.  The gardens included a lovely reflecting pool and fountain, and a flagstone terrace that offered a vista overlooking downtown.

The gardens included a lovely reflecting pool and fountain, and a flagstone terrace that offered a vista overlooking downtown.

At the handsome café inside the new visitors' center, I interviewed the three women working behind the counter. Two were in their early twenties. One had straight, dark, shoulder-length hair, and a heavy dose of purple eye shadow above her brown eyes. The other had straight black hair down to the middle of her back. She wore jeans, and glasses rested on her large Roman nose.

The third woman was older. She had light brown eyes, full red lips, and a round button nose; her light brown hair was pulled over each ear and curled around her neck. Tan overalls tented her small wiry body, and short, baby-like forearms extended from the sleeves of her white T-shirt that (like her coworkers') bore the name and logo of her catering company employer.

To my question whether people in Youngstown were isolated like Hopper's characters, the older woman barked, "Yeah."

The girl with glasses answered, "I think so because we're not a big city so we don't see a lot of culture. What we call culture is just, like, junk."

The older woman sneered, "If you're a cultural institution looking at this part of the country, why not set up in Cleveland or in Pittsburgh; why choose Youngstown?"

"Youngstown is cleaning up," the mascaraed girl offered.

The girl in glasses agreed, "Yeah, they cleaned it up."

"They tried to bring back the Youngstown area," the older woman scoffed, "but I don't think that it's ever going to come back. Once you get a huge influx of organized crime, forget it."

"I don't know," interrupted the mascaraed girl. "I don't think we're isolated from each other. I think we're isolated from the rest of the world, yeah." She added with a shrug and a giggle, "I like it here. People are friendly here. I feel comfortable here. We don't want to like put it down. You know what it's like: we can put it down, but it's our town. I grew up here my whole life," she said to the older woman. "You haven't."

"See," The older woman countered, "I've lived elsewhere and she hasn't. I have a daughter the same age as these girls I am working with."

"Why are you here?" I asked.

"Why do I live here?" she said as if she were asking herself. "My husband got transferred here. But my life situation is changing, so hopefully in the next few years I can move out west someplace where I'm comfortable. It's where I come from."

"I noticed that different churches are side-by-side. That gives me the impression that it is a little bit isolated, that communities don't mix."

"I never contemplated that," the mascaraed girl considered "but yeah."

"Well, yeah," the girl in glasses added, "There's a lot of different denominations. Ethnic groups do tend to stay to themselves in Youngstown. Some of these people still only speak the one language. They like to stay in one area. There's not a lot of mixing. They have a lot of family here. You know, grandkids take care of their grandparents."

"There is that tradition," her younger counterpart agreed. "Maybe it's really a good community; a lot of people have lived here all their life."

The girl in glasses laughed. "Either it's all they know, or they are tight because they're inbred."

The older woman shook her head, "The city is hideous. But the park is just wonderful. Take a peek in the library before you go. There's a display about the park history."

"I didn't know that," the mascaraed girl exclaimed. "See, that's interesting that I didn't know about that, and it's right here. The best part of Youngstown is right here."

20090220

160 Youngstown, OH: The Vindicator

For a town whose local newspaper was called the Vindicator, appropriately, its most famous resident was a defiant politician, James Traficant. Traficant's plastered hair and huge sideburns made him memorable from photos taken outside his many court battles. In the early 1980s, Traficant became the first person to beat a federal racketeering rap without a lawyer, despite the fact that the Feds had a signed confession from Traficant and tapes of him assuring the mob, "You're just like family to me." Traficant claimed he was conducting his own "sting."

"Jim's the guy pointing our middle finger at Washington," said a local radio-talk-show host. "Youngstown's getting slaughtered, but the attitude is, we're going down defiantly in a blaze of glory." After the Internal Revenue Service forced Traficant to pay $180,000 in back taxes, he crafted a 1998 bill that severely curtailed the IRS's powers. Traficant's legend grew when he spent three days in jail for refusing to enforce foreclosure orders against local unemployed homeowners. He had been elected to eight terms.

As a reaction, some locals organized the reform-minded Youngstown Citizens League. The FBI beefed up the number of agents in Youngstown. The FBI Mob specialist assigned to the beat said, "This community is probably more involved in politics than any place I've ever seen. Everybody has an opinion and everybody voices it." In 2002, Traficant was finally found guilty, but the tangible effects of public corruption and incompetence linger everywhere in the Mahoning Valley. The state took over the city schools. Roads were potholed. Accused murderers were allegedly freed because they paid off judges and lawyers. George McKelvey, Youngstown's mayor since 1998, said, "The cancer came close to destroying this community."

The Mahoning County Courthouse is adorned with the words "where law ends tyranny begins."

20090219

159 Youngstown, OH: The Butler's Butler

On my way out the door, I noticed the guard, who I had seen on a previous visit when I sidetracked from Cleveland specifically to see the Butler. He was a stocky, cheery African American guy with graying five o'clock shadow on the bottom of his round head and dark stubble on top of it. His nametag said "Wallace."

"Yeah," he answered, "You're pretty much isolated in the city, if you stayed. Everybody's out in the suburbs. They go out there just to get away, to be isolated. There's not too much exchange between people. It's people you know who you talk to: you went to school together, or we know each other; or we grew up then he moved out of the neighborhood. They're not connected other than that."

"Did you grow up in Youngstown?"

"Yes," he said formally, "yes, I did."

"I hate to shoot from the hip, but what about black-white relations in this town?"

"Yeah, okay, black and white relations in this town? It's okay. I was taught to learn how to deal with all creeds, colors, and nationalities. That's the way I was brought up. Okay? Now I guess there's this young generation that's coming up. Do you know this music they're listening to? They're angry. I'm like, 'Whatever is wrong, whatever it is, whatever had happened, forget about it.' That was over a hundred years ago. You know, now it's a new day, a new time.

"If anyone would have told me that it would have been like this twenty-five years ago, I would have never believed it. 'Cause, I'm saying, it was going in the right direction. But you got the kids with peer pressure, which is hell these days. When I was growing up the only peer pressure you had was worrying about drinking a beer and smoking a little marijuana. Now you have AIDS, you have crack, you have gangs. There's guns. It's serious.

"It just does not make any sense. Everybody should just stick together and work together and look at the bright side. And worry about these other nations that are taking jobs away. You have congressmen, who these people are signing it away. My father was a steel guy. He loved the mill. When they shut that mill down, they killed my father. Hundreds of people's fathers. This is what they went to war for. They turn over in their graves, to have today the leading nation in steel be foreign. What's going to happen if there's a major war break out? What are we going to do? Wait to go overseas to get the steel, and we're fighting against the ones that have it?"

Wallace stopped short to bid "Bye bye" to a woman leaving the museum.

"I love Edward Hopper paintings," he assured me. "I would like to go to The Art Institute of Chicago and see the one there. Nighthawks. Quite a few paintings I'd like to see in Chicago, like George Seurat.  The one where they're at the picnic and on the beach. That thing just blows me away, to see a little picture of it. I can only imagine how it looks as big as that wall. But I'm here. Six days a week workin' here. Been here seventeen years. Tryin', you know."

The one where they're at the picnic and on the beach. That thing just blows me away, to see a little picture of it. I can only imagine how it looks as big as that wall. But I'm here. Six days a week workin' here. Been here seventeen years. Tryin', you know."

20090218

158 Youngstown, OH: Drydocked

At the card shop, I bought a post card of Pennsylvania Coal Town that put Hopper's name under the reproduction in large letters, as if it were on a theater marquee. The frail but spirited older woman behind the counter wore black pants and a pink sweater with pink embroidered roses on it. She had wispy hair and tortoise-shell glasses, and she rocked from her front foot to her back as she answered my question.

"No, I don't think so," she said emphatically but reassuringly. "You mean isolated from the rest of the country? People in Youngstown travel within the country and also abroad. Of course, as in every city, you find people who probably have never gone outside Youngstown.

"In general, people are very friendly, very nice, good people. Even though you hear awful things about Youngstown and how many people were killed this week, there's lots to recommend Youngstown, I think. The only thing is it's in the middle of Ohio. I grew up in Australia about twenty miles from the Pacific Ocean. And then I came to landlocked Youngstown. So it seems I've been here for quite a long time. I had no idea I'd miss the ocean as much as I still do. I think it gets into your blood somehow.

"There's a lot of unemployment [here] and a lot of poverty, as there is anywhere. When the mills closed, this--Pittsburgh, Youngstown and Cleveland--was what they used to call the diamond ... the golden triangle ... the diamond triangle, I think it was. With all the incredible steel industry here. It's gone."

"What about the other meaning of that word?" I asked.

"Which word are we talking about?" she asked.

"Isolation. Are the people isolated from each other?"

"Oh no," she said. "I think there are not a great number, but a diversity of ethnic international groups. And of course we have people who are well-trained professionals who are, through the job, taking advantage of the education that's offered near here. Other people kind of give up. But then there are also white people who give up, too. It depends. I often think, 'How would I act if I were in a situation where I felt I had not much control?' (I'm not speaking of black or white here, but in any case, it would be very difficult.) But then there are other people who rise above it through all kinds of situations. As I say, there's poverty,  but there's poverty everywhere, and people try to do things to help.

but there's poverty everywhere, and people try to do things to help.

"We have, up here, the Arms Historical Museum," she continued. "We have downtown, and then the Youngstown Symphony Society, which is a very good symphony. Mill Creek Park, which is really incredible. I could live in that Mill Creek library forever; just sit in the chair there and look out the window. It's a smallish town comparatively. Whereas, if it were the size of New York, you wouldn't even hear about these things.

"We have The Butler, which is open to all people free of charge. The kids are really very cute. I was standing out in the central hall, and a woman and her daughter looked a little as if they needed some directions. And I said, 'Are you familiar with the museum?', and the mother said, 'No, I'm not.' And the little girl said, 'But I am.' She was so proud, you know. She had come with her school, then she got her mother to come, too."